Ferrari’s Mark on NZ Motorsport

Motoring writer Donn Anderson recalls some memorable Ferrari moments and events in more than 50 years of local motor racing ...

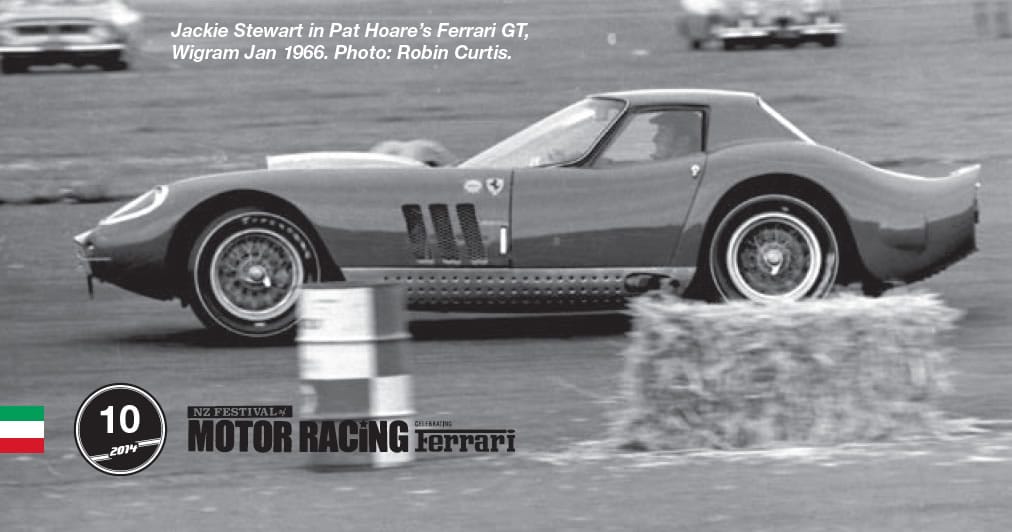

Christchurch Ferrari importer Pat Hoare had any inkling as to the future value of racing Ferraris, he would never have contemplated the conversion of his Ferrari Dino 246 Formula 1 open wheeler into an enclosed GT road car 50 years ago. But then, as we all know, hindsight is a wonderful thing.

In 1964 the Tasman Cup championship had just kicked off, and Hoare’s 2953cc V12-engined 246 did not comply with the new 2.5-litre engine capacity limit. Besides, while Pat had won the 1962 Gold Star championship with the car, it was now an outdated frontengined machine when the new trend was clearly for rear-engined designs.

So he did what would today be unthinkable — he converted the single-seater into a GT special to produce what Enzo Ferrari described at the time was ‘probably the world’s quickest road-equipped Ferrari’. It ended up a slightly ungainly looking beast that was too long in the bonnet and too short in the tail.

Nevertheless, BRM works driver Jackie Stewart, who of course went on to much greater things, sampled the Hoare Ferrari GT special at the 1966 Lady Wigram trophy meeting.

He did several laps of the airfield circuit and was impressed after pushing the car hard and fast. As a works machine, the Hoare Ferrari came with a pedigree that included world champion Phil Hill winning the 1960 Italian Grand Prix at Monza — the last Formula 1 race to be won by a front-engined racer.

Hoare wanted to base the road car on the Ferrari GTO and wrote to the factory to obtain blueprints and data. It was obvious not all parts could be obtained or made in New Zealand and a few items, such as the large, sharply raked windscreen, were acquired from Ferrari. Pat was keen to have as much of the racing car remain, and the building of the GT did not mean simply using bits and pieces off the single-seater, but actually building the car around the racing chassis.

The problems were numerous. The wheelbase of the racing car was six inches shorter than that of the GTO and the plans had to be scaled down with the measurements converted from metric scales to inches. A Christchurch architect set about producing the plans from those of the original GTO blueprints and mechanic Ernie Ransley, who had been associated with Hoare for much of his racing career, began work on removing the openwheeler body.

Alterations had to be made to the steering and other controls to transform the car to a right-hand-drive vehicle. Hec Green, who had been responsible for several local specials, built the tubular framework to take the body — a long task due to the hair-splitting accuracy of every detail. G.B. McWhinnie and company set about making the bodywork from 16 gauge aluminium sheeting, completing the job in little more than two months. The numerous compound curves on the body demanded work of world class by the coachbuilders and the end result was rather good.

Hoare was keen to have only the best trim for his car, and much of this work was completed by George Lee, who was an 18-yearold apprentice for McWhinnies at the time.

Finished in high-quality leather, the central armrest console and door panels were pleated and liberal padding covered the top facia edge. McWhinnies also went to considerable pains with the paintwork which, of course, had to be red.

The end result was a rapid road car, with the 330 bhp V12 Testa Rossa wet sump sports car engine located exactly as it had been in the racing car, with its magneto ignition and six Weber 38DCE carburettors. A multi-plate clutch was used for the five-speed, close ratio gearbox, the rear suspension was independent by coil springs, and Koni shock absorbers provided the damping. Firestone racing tyres were fitted to the 15-inch wire wheels, and twin pipes protruded from either side of the bodywork.

The cockpit arrangement was unusual with most instruments located on the passenger side of the facia, and the 10,000 tachometer red-lined at 8000 rpm. There was a 160 miles an hour speedo and gauges for fuel pressure, oil pressure and oil temperature. Most controls were sited in the centre above the transmission console.

Practical this car was not, with difficult access to a cramped cockpit that had little headroom and closely spaced pedals. Occupants also had to put up with no load space and a harsh slow speed ride. The Hoare Ferrari GT was 90 kg, or around 200 lb, heavier than the old racing car, yet still much lighter than the works GTOs. It was geared for a higher top speed than the single-seater but more modest acceleration. The wind-cheating shape and light body gave it an estimated maximum speed of around 290 km/h (180 mph) which was reputed to be better than the GTO. The fastest official speed of 249.6 km/h in the car was achieved by Donald McDonald in 1969. As has been the destiny of so many Ferraris in New Zealand, the Hoare GT would disappear off shore. It was converted back to single-seater status by Neil Corner in Britain.

Other racing Ferraris have been converted to road use only to be returned to their original status. Ferris de Joux acquired Ron Roycroft’s early ’fifties Ferrari 375 single-seater, less engine, and spent more than two years creating a handsome two-door sedan powered by a twin-cam Jaguar XK engine. Years later it was back as a single-seater in an Italian museum.

A shortage of new cars and sometimes parts often led New Zealanders into improvising their machines. When John Riley’s ex-Ken Wharton Monza Ferrari sports car suffered a major engine failure, the car was fitted with a 4.6-litre Corvette V8.

New Zealand has witnessed a host of Ferrari sagas. There was the amazing Morrari Allcomer saloon, raced by the late Garth Souness and labelled ‘the sensation of ’64’.

While externally it looked like an early lowheadlight Morris Minor, it was built on a Ferrari Tipo 555 Super Squalo spaceframe chassis previously raced by Englishman Peter Whitehead and Tom Clark. Souness acquired the car from Bob Smith and it sat in his car yard for some time before he decided to convert the Italian classic into a racing saloon. He fitted it out with a 327 Corvette motor and sold the Ferrari power unit to Len Southward. After two seasons Gavin Bain bought the Morrari and the chassis eventually found its way to the UK, and now resides in Spain as the original Tipo 555.

Chris Amon, arguably the fastest man never to win a world championship F1 race, was a delight in both the 1968 and 1969 Tasman Cup series. At the time Chris was a works Ferrari driver — the only New Zealander to fill such a coveted seat — and he was a treat to watch on local circuits in the good-looking Formula 2-based Ferrari Dino 246T. He won the 1969 Tasman championship, and the following year Hamilton driver Graeme Lawrence took the same car to victory in the eight-round Australasian series.

Soon after he took delivery in late 1969 Graeme said, ‘Right from the time I first sat in the car it felt just right. You would have thought the cockpit had been measured up for me as there is good arm, leg and pedal room.’ After 500 kilometres of testing he felt confident and pleased with the performance. ‘Engineering and finish on the mechanical side of the car is superb. I never realised how good the Ferrari is in the major parts where it really matters — the suspension looks so fine, but is exceptionally strong,’ said Lawrence. The engine had been claimed to produce 300 bhp, but dyno testing in Sydney during the Australian Tasman rounds revealed an output of around 275 bhp.

Aussie Spencer Martin raced the beautiful looking Scuderia Veloce Ferrari 250LM here in 1966, winning the sports car races at the Pukekohe Grand Prix meeting, Lady Wigram and Teretonga. Masterton farmer Andrew Buchanan raced the same machine in local sports car events in 1967. New Zealanders Ross Jensen, Ken Harris, Logan Fow, Frank Shuter, Bill Thomasen have all raced Ferraris on their home turf.

That the Italian marque is special goes without saying. Ferraris have been an important part of local motor racing for more than half a century, and it is fitting that the Hampton Downs Festival of Motor Racing pays tribute to these wonderful cars — both race and road — this year. Enjoy the moment.

No Comments