Can-Am 1969 with Chris Amon

A driver with extraordinary ability.

By Bill Gavin

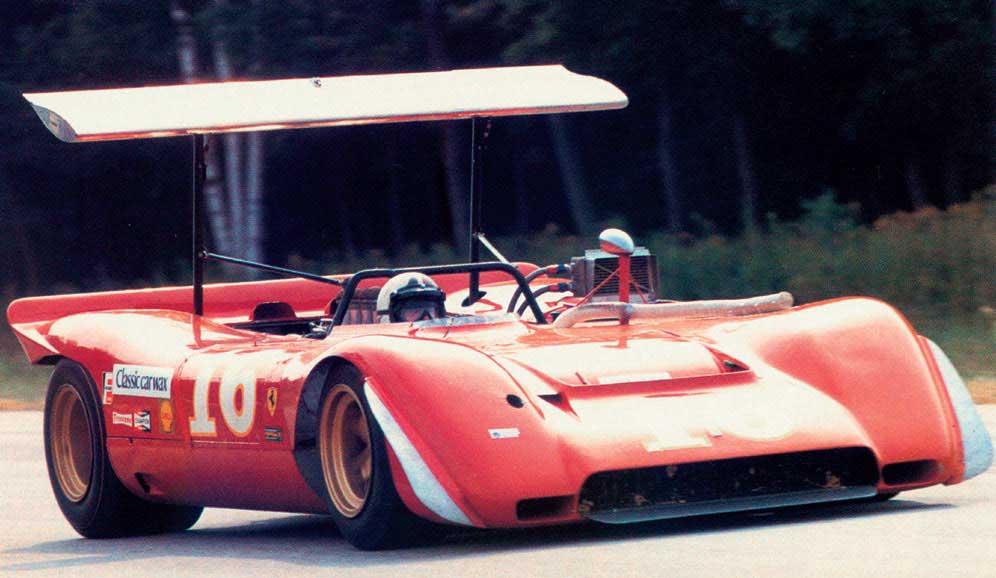

Photo Above: Chris Amon in his 1969 Ferrari 612 Can-Am. (Photo from Chris Amon collection in book Champions of Speed p167)

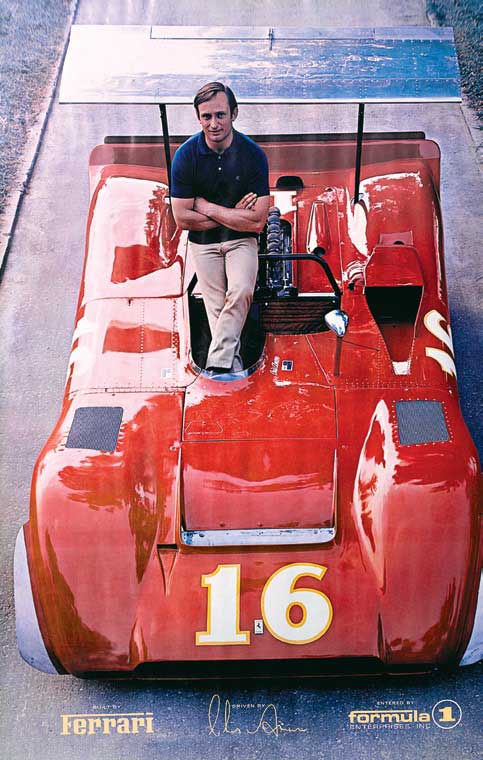

In April of 1969 at the Spanish Grand Prix at the Montjuïc circuit in Barcelona, Chris Amon told me about his plans for the Can-Am series. Ferrari had modified and lightened the 6.2 litre V12 based on the 512 prototype which had run just once at Las Vegas in 1968, and had agreed to let Chris run the team himself as he had recently done so successfully in winning the Tasman series with the 2-litre Dino car. That Enzo Ferrari would do this for a driver was confirmation of the enormous respect that the old man had for Chris, even though in three seasons at Ferrari he had never won a Grand Prix, and now again at Montjuïc he was to lead the race by half a minute ahead of eventual winner Jackie Stewart when his engine blew.

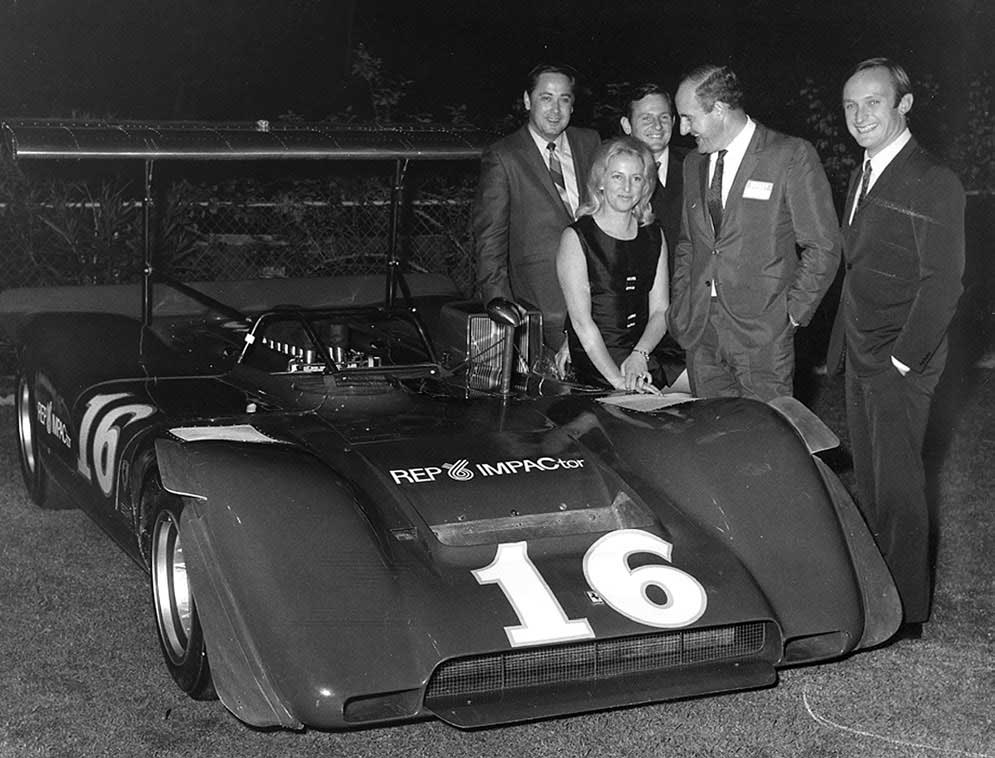

I was really surprised when Chris said he would like me to manage the Can-Am team – as a freelance journalist I had made a specialty of covering the Can-Am races from 1966 and also the unofficial Fall Series that preceded it from 1963, so I knew my way around the circuits of North America and understood Can-Am racing which I had once described (perhaps unkindly) as two-seater Formula Libre, but team management was outside my experience. But it was an enormously exciting proposition, so I abandoned the writing projects I was working on, including the ghosting of the autobiography of current World Champion

Graham Hill.

We based the team in Michigan, close to any engineering support needed (and to McLaren), and with help from my former editor at Car and Driver, David E Davis Jr, found a large house at Pine Lake some miles north of Detroit. Mechanics Roger Bailey and Norm Lockwood stayed there, along with my wife Jane, my year-old son and his nanny, and Chris stayed with us from time to time. The Ferrari agent in Los Angeles, Chick Vandagriff, was providing a truck and trailer, and his mechanic Doane Spencer, plus Chick’s teenage son Cris made up the team.

We based the team in Michigan, close to any engineering support needed (and to McLaren), and with help from my former editor at Car and Driver, David E Davis Jr, found a large house at Pine Lake some miles north of Detroit. Mechanics Roger Bailey and Norm Lockwood stayed there, along with my wife Jane, my year-old son and his nanny, and Chris stayed with us from time to time. The Ferrari agent in Los Angeles, Chick Vandagriff, was providing a truck and trailer, and his mechanic Doane Spencer, plus Chick’s teenage son Cris made up the team.

The Series started badly when the 612 got lost at JFK airport – just how a bright-red Ferrari on a pallet can get lost I never figured out, but it was found after three days in a TWA hangar having been flown in by Alitalia. That put paid to the planned testing at Watkins Glen, but nevertheless Chris qualified the car third and finished third behind Bruce McLaren and Denny Hulme in their all-conquering McLaren M8Bs with their huge aluminium Chevrolet V8s.

It was to become a regular sight at Can-Am races that year, three Kiwis running 1-2-3 at the head of the field; Chris occasionally leading and finishing second once, at Edmonton, then third again at Mid-Ohio. This was followed by a series of failures to start or finish caused by oil-feed problems to the V12 engines, both in the 6.2s we had for seven races and then in the 6.9-litre that arrived in time for the final races at Riverside and College Station, Texas.

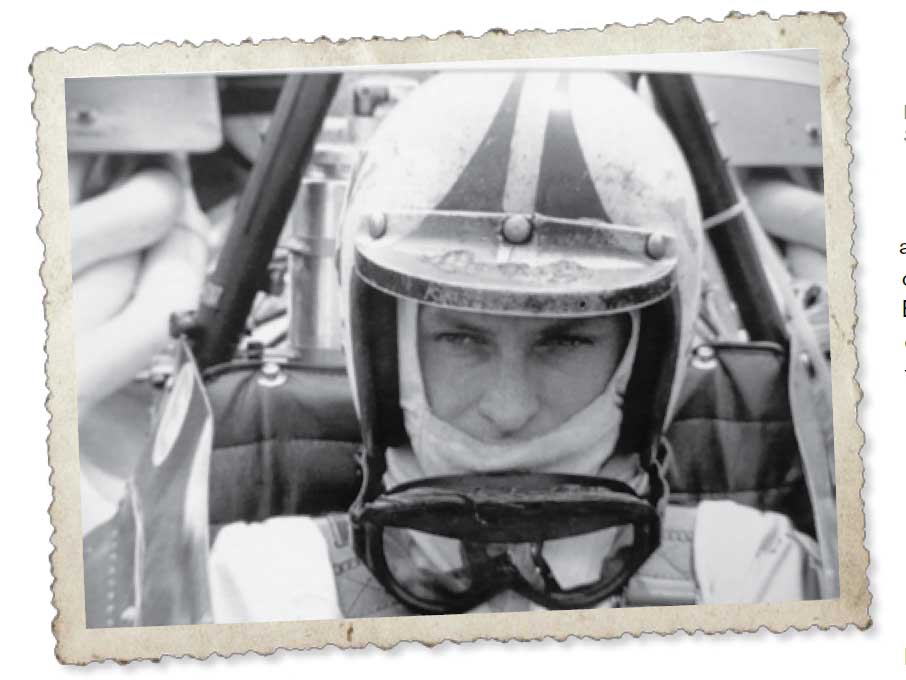

Although we were both New Zealanders, I had not known Chris well, and he tells me that the last New Zealand race meeting I covered for the Auckland Star 8 O’Clock edition, the Levin Easter event in 1960, was his first race with the A40 Special. I had first met him at Spa-Francorchamps and saw him drive in what was effectively a works Lola – he was just 19 years old. On this most dangerous of all the European circuits, Chris qualified 15th on the grid, was 10th at the end of the first lap, then passed Tony Maggs in the works Cooper, and Richie Ginther in the works BRM, to run in seventh place by the seventh lap, only to lose oil pressure and retire on the 10th lap. In Autocourse I described it as ‘his brilliant Grande Epreuve debut’ – had his car kept running he would have finished fourth and scored points in his first World Championship Grand Prix – it was the sort of effort that gets today’s TV commentators very excited while the procession at the front marches on.

But although Reg Parnell had recognized Chris’s talents and put him a in a F1 car, the team was not successful. In the championship races for the Parnell team over three seasons, Chris finished only five times in 19 starts.

But it was at Ferrari that his talent became clear, and for three years he consistently qualified the cars on pole, on the front row of the grid or close to it. But real success eluded him and the media in general described him as unlucky, but I was privileged to be able to measure his talents by what his competitors had to say about him – they all acknowledged his extraordinary ability.

In that ’69 Can-Am season it was at Mid-Ohio that Chris impressed me more than any other time – he had missed the first day’s practice having been delayed in Europe, and was tired and unwell. He had never seen the circuit, and the car was running gear ratios selected by Roger as I drove him around the track in our LTD loaned by Ford, yet after a mere handful of laps Chris was down to the times of Bruce and Denny who had been testing at the track a few days previously.

In that ’69 Can-Am season it was at Mid-Ohio that Chris impressed me more than any other time – he had missed the first day’s practice having been delayed in Europe, and was tired and unwell. He had never seen the circuit, and the car was running gear ratios selected by Roger as I drove him around the track in our LTD loaned by Ford, yet after a mere handful of laps Chris was down to the times of Bruce and Denny who had been testing at the track a few days previously.

He possibly had more natural ability than anybody who ever got into a racing car, and this had been evident from his early drives in the ex-Owen Organisation’s Maserati 250F and later the ex-Bruce McLaren Sebring-winning Cooper T51 Climax here in New Zealand and Australia. In terms of natural ability the only drivers of the ‘1960s to whom I would compare him were Stirling Moss, Jim Clark and possibly Jochen Rindt. I am told that in the Tasman series of 1968 he had appeared to have the measure of Jimmy.

Chris had already made up his mind to leave Ferrari during that Can-Am series, and there followed the years with March, Matra, Tecno, Amon, Ensign and others. He won non-championship races for March and Matra, and gained many podiums for both in the Championships from 1970 through 1972. In the next four years success eluded him.

I lost touch with Chris as I established a new career in the film industry, and didn’t catch up with him until I moved back to New Zealand in the early 1990s. This was a different Chris – he had a great wife, three great teenage children, and was milking 800 cows. Once as we reminisced in the early hours at his farm at Scotts Ferry, Chris told me how, although he usually qualified way down the grid in those last years, he often passed many who had qualified ahead of him and sometimes reached a major placing before the car expired. I had not been following racing closely in this period, my weekly reading being Variety rather than Autosport, so when I got back to Auckland I delved into my Autocourse collection which gave the position, lap time and elapsed time of every car in every Grand Prix. I was delighted to find that Chris was right, that his talent and determination were there to the end of his career.

In that ’69 year at Pine Lake, at the races, and later when we shared a suite at the Chateau Marmont on Sunset Strip when doing the West Coast races, I got to know more about this remarkable man. I remember him as somebody very special – he was young, he was handsome, and he drove for Ferrari. He enjoyed his racing and he enjoyed life – other drivers had more success from their dour endeavours, but few lives were so enriched as Chris Amon’s. Here was a man who enjoyed a drink and the company of beautiful women, yet was an assiduous

worker – he must have put in more miles testing for Firestone, McLaren, Ferrari and others than any other driver of that period, and those who worked with him say he was brilliant at it.

Looking at the Autocourse top 10 rankings of that year, only five of the 10 drivers survived their racing careers. Many say Chris was the unluckiest of drivers. He feels that he was the lucky one – he survived accidents which could easily have killed him.

We share his luck in that he’s here with us still, fit and well, a surviving star of the deadliest period in Grand Prix racing.

Bill Gavin was a motor racing writer in the 1960s and managed the Ferrari Can Am challenge in 1969. Nowadays better known in New Zealand as a producer of such films as What Becomes of the Broken Hearted?, Jubilee and Whale Rider, he is now writing Love, Life And Death In The ’Sixties a forthright motor-racing memoir.

Source: NZFMR 2011, Can-Am 1969 with Chris Amon -Page 10,11,12

Steve Scheier

Posted at 08:11h, 28 JanuaryI had the pleasure of watching Chris drive the Ferrari 612P at Road America in 1969. Chris ran third for most of the race behind Denny Hulme and the eventual winner, Bruce Mclaren. I will always remember the beautiful song of the Ferrari V12 engine and Chris Amon’s determined driving.